Samuel Colt's Competition from Abroad, Robert Adams Revolver

Read More Articles:

Robert Adam's Quality Design Managed

To Rid The British Market Of American Competition

(Originally Published in the Civil War Courier)

Of the many arms imported from Europe during the 1850s and 1860s, there were only a few that were considered worthy of service in the United States and Confederate Armies. A prime example is the Adams Revolver.

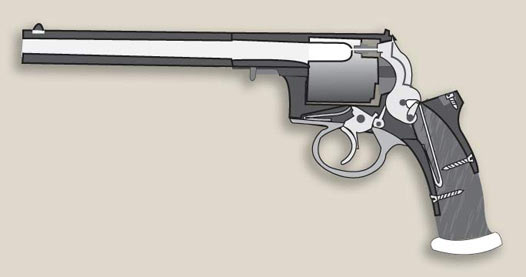

This five shot, self-cocking revolver was invented by the Englishman Robert Adams. At the time of the weapon's initial creation, he was manager for the London House of George & John Deane. This company was well respected in the trade, but it was the Great Exhibition of 1851 which brought Adam's invention to prominence. The firearm won a prize medal in the category of double and single guns and pistols properly finished.

Subsequently, Adams went into partnership with John Deane, Jr. and Sr. to form Deane, Adams and Deane, the company that originally produced Adams invention. The company's office was based in Bermondsey, and had a factory on Weston Street .

On August 22, 1851, Robert Adams earned an English Patent for his Revolver. These early models, that were produced in Pocket, Navy and dragoon sizes, lacked a few important amenities which made the design somewhat unpopular. They had no recoil shield behind the cylinder, which meant that the shooter was often subjected to back flash. The early models also lacked a rammer, Samuel Colt's fine arms utilized this feature quite efficiently. Therefore when loading the wadded bullets in the Adams, they had to be thumb pressed into the chamber. This method of loading sometimes caused the bullets to jar forward and leave a gap ahead of the powder charge.

In addition to the deficiency of a recoil shield and rammer, the early arms were also missing a hammer spur, which meant that they could not be hand cocked. This was also a feature which the Colt had. Of course, the Colt was a single action.

To determine which revolver was the better arm, firing tests were held at Woolwich, England in September of 1851. Amazingly, the Adams was the favored weapon because the Dragoon Colt was viewed as too clumsy and the Adams could shoot faster. However, further trials were conducted in South Africa in 1852. In this contest, Colt's arms proved to be, by far, the superior.

The successful field trials only further convinced Colt that it would be a wise idea to secure a hold on the English Market. He had already registered for British Patents on his design as early as 1835. In 1853 the factory in London was producing the 1849 pocket, as well as the 1851 Navy revolver. This was a very smart move indeed, because as a result, the British Navy ordered 9500 Colt Navy models. The British Army followed suit two years later by purchasing an additional 14,000 Navy models. Most likely the British decision to purchase Colt's arms resulted from a distrust of the Adam's self-cocking lock mechanism. It was believed that the weapon could not withstand the riggers of combat. Even more to the point, Colt's powerful lever rammer placed the bullets safely in the chamber so they would not be knocked lose from the chambers.

Even though Adam's did not initially achieve a substantial service contract, the company was still highly successful. Adams, who was definitely a pragmatist, recognized where the strength of his sales lay. So much so that the London Factory was unable to keep up with the demand found in the commercial market. In fact some production was contracted to William Tranter, along with the company of Hollis & Sheath whose foundries were all located in Birmingham, England. Countering Colt's factory in England, Adams took the initiative to patent his arm in the U.S. in May of 1853 in hopes of breaking into the commercial market there.

Surprisingly though, the United States Ordnance Department did not become aware of the arm on its own turf. Nor was it discovered in Great Britain. You see, in addition to the license agreements in England, Adams also licensed the arm to Auguste Francotte, in Liege Belgium. It was there that Major Alfred Mordecai of the Ordnance Corps noticed it. He was on a trip abroad in 1854 when he purchased the Belgian weapon. He drew a very detailed illustration of the Adams self-cocking mechanism. Mordecai commented on the arm, "The workmanship of the pistol is very good, and the arm appears to have met with much favor; but it still wants the test of actual service, and it may be doubted whether it is expedient to arm any part of the troops with a weapon which can be discharged with such exceeding facility and rapidity. It is understood that some of these pistols have been ordered by the Ordnance Department, for trial in our service. At present they are sold at about 2/3rds of the cost of Colt's revolver."1

The most serious shortcomings of the early arms were quickly alleviated on February 20, 1855 when another British patent was given to Lt. Frederick Beaumont. Beaumont was from the Royal British Engineers. His improvements involved a trigger-hammer linkage which gave the Adams the capability of single action, in addition to self-cocking fire. This made it one of the first double action arms.

James Kerr furthered the weapon's progress by creating a well designed loading lever. The beauty of this design was that the lever lay alongside the left side of the barrel. The lever swivelled on a screw which was an extension of a barrel lug. That is opposed to Colt's loading lever which lay under the barrel. This difference was extremely significant because there was no legal discourse Colt could take to stop production of the new Adams-Beaumont arm.

Another significant difference between the competitors operating mechanisms involved the mechanical rotation of the cylinder. The Colt's action of the hammer moved the cylinder by use of a spring, thus the movement was prone to break. The Adams on the other had a cylinder bolt that was incorporated into the trigger. It rested on top of the trigger body just behind the trigger's pivot point. Upon pulling the trigger to the rear the bolt acted in unison with the upraised pawl pressing against a ratchet tooth. This locked the cylinder into position. Thus, the trigger action effected the cylinder rotation which moved from left to right. This was a much more trustworthy system. However, the dependable movement led to one of the revolver's flaws. Because of the lump on the top of the trigger it was impossible to add a sixth chamber.

The improvements which resulted in the Adams-Beaumont revolver earned Deane Adams and Deane, the chance for more service trials by the British. It was decided that the Adams-Beaumont arm was of equal quality to the Colt even though it still lacked a recoil shield. Moreover, due to its solid frame and durable cylinder mechanism, the improved arm was regarded as superior to the Colt for military service. The most important aspect of the Adams was its solid frame construction. The solid frame was more durable because it forged the barrel, frame and butt from one solid piece of metal. An opening was cut into the frame to allow the cylinder to be inserted. As a result the barrel was more firmly attached to the frame by a top strap, which passed across the top of the cylinder to the standing breech, the portion of the frame behind the cylinder.

In October of 1855 some substantial orders for the arm were placed to satisfy the needs created by the Crimean War. Yet the war ended before the order was completed. Both the Colt and the Adams did see service in this war, along with practical use in India. Fortunately for Adams, his arm was found to be superior in active duty.

In a sense though, this success brought ultimate destruction to the company of Deane Adams & Deane. In August of 1856 the firm broke up and Robert Adams transferred his patents, along with his services, to a new company. The London Armoury Company was formed by city merchants, and Adams found himself in the position of superintendent. Offices for the London Armoury Company were located at 36 King William Street in London.

Deane Adams & Deane's demise did work out in England's best business interests, though. The improved Adams was successful in ending the near-monopoly held by Colt in the British Market. In fact, by 1857 he was forced to close down his British factory. This partly stemmed from the expiration of his patents.

The London Arms Company's large factory could be found in Bermondsey on Henry Street, which was not far from the offices. This manufacturing plant was located in what is believed to have been a former railway shop. The property was purchased from the South Eastern Railway Company which has helped to determine this. Moreover, the structure has been referred to as "the Railway Arches."

It is interesting to note, that prior to the War Between the States, the London Arms Company purchased a great deal of machinery from the Ames Manufacturing Company of Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts. This was because the Ames Company was renowned for its woodworking machinery. However, this machinery had little, if anything to do with the production of Adams Revolvers. For the most part it was used for the creation of interchangeable Enfield Rifles. In addition to the famous muzzle loading rifles and Adams Revolvers, the London Armoury Company also produced Kerr revolvers, for the British Government.

The Adams' introduction into the United States became more mainstream in June of 1856 when Lieutenant Beaumont received a US patent for his double action mechanism. A little less than a year later, James Kerr was also issued a patent. This opened the door to some new options for Adam's invention.

The London Armoury Company attempted to break into the United States Ordnance Market by sending Major R.S. Ripley to New York City in June of 1856. The U.S. Ordnance department wanted to see them in the same caliber of the Colt Navy model which was .36. This was not a standard bore size for the Adams Revolvers which came in .497 caliber with a barrel of 7½", .442 caliber and a barrel length of 6¼" and .338 caliber with a barrel length 4½". Therefore the arms needed to be custom made and this took some time. In early March 1857 one-hundred English Adams revolvers along with ammunition and replacement parts were presented to New York Arsenal. Eighty-eight of these were distributed to the Army.

It is believed that the eighty-eight revolvers issued in 1857 were similar to those later used by the Union during the Civil War. They had six inch octagonal barrels, and had a caliber with the Colt of .36. However, arms obtained from abroad for war time procurement were generally the British standard of .44 caliber. These percussion revolvers all had black walnut saw handles with a large hump to prevent the shooter's hand from slipping up. They were also equipped with a spring safety.

The Ordnance Department quickly grew tired of waiting for shipments from across the Atlantic. In August of 1857, Duncan Ingraham Chief of Ordnance canceled an order of 50 Adams revolvers intended for the Navy. This was due to a four month delay in receipt of the arms.

Fortunately though, the London Arms Company had the foresight to create a licensing agreement with the Massachusetts Arms Company to create arms in .36 and .31 calibers. The ordnance department ordered 500 such arms a month after receiving the initial 100 English made revolvers. The initial shipment finally arrived at the New York Arsenal in July of 1858 and the final shipment arrived in September.2 The pistols manufactured by the Massachusetts Arms Company in Chicopee Falls alleviated the problem resulting from the lack of a recoil shield. These arms added a flange plate on the left side behind the percussion cones.

One-hundred-nine additional belt size Adams revolvers were produced above and beyond the 500 made for the U.S. Ordnance Department. However, the Massachusetts Arms Company did not manufacture any more of this caliber Adams Revolver. The company did continue to produce the .31 caliber pocket model. They then shifted their concentration to the production of Maynard Carbines.

The United States stuck to their guns, (pardon the cliché), and favored the Colt Models over the Adams-Beaumont. However, at a time when both the North and South were trying to arm themselves as quickly as possible, a variety of foreign sources came into play. The New York City firm of Schuyler, Hartley and Graham were the predominant importers of the arms for the United States. Between August 1861 and April 1862 they sold the Union a total of 795 revolvers at a cost of $18 each. Actually, $18 was the general rate for the weapons from all sources leading up to and during the war. A grand total of 1,075 Adams Revolvers were purchased by the Union during the war.

There are two U.S. units known to have carried the arm. The first of which was the 8th Pennsylvania Cavalry. They did some great reconnaissance work around the Richmond area during the battle for Richmond. The 2nd Michigan Cavalry was also issued a few Adams revolvers in September of 1863.

The Southern states were really no stranger to the weapon either. Early in 1861 the State of Virginia received just under 1000 Deane & Adams revolvers. Some of these went to Colonel Chilton at Ashland Virginia. The 5th Virginia Cavalry was also armed with Adams. As was the 1st Virginia Cavalry.

Georgia procured 400 Adams Army revolvers along with a rather substantial number of Colts. Alabama purchased 100 fewer through the firm of Schuyler, Hartley and Graham. 3

By far, the most famous Southerners to be known to possess the all important Adams revolvers were Jeb B. Magruder and "Stonewall" Jackson. The tale of General Magruder's prized arm states that a Confederate sympathizer visited Marcellus Hartley's Maiden Lane Store in New York. He returned to Dixie with an elegant case that was intricately engraved. In addition to enclosing a great pistol, the case also included German-silver flasks, moulds and accessories. 4

Adams was ousted from his position as Superintendent for the London Armoury Company in 1859. He continued to produce his revolvers in Birmingham, England at 76 King Street. Therefore, he must have still held the patents. His setback with the London Armoury Company apparently did not dissuade him from continuing to create innovative arms. In 1862 he won another award at London's International Exhibition for a shotgun he invented.

For a brief time, the London Armoury Company continued to prosper. He moved to a new location in 1863. They continued to produce the Beaumont-Adams revolver until 1867 when the firm went out of business.

Endnotes

1. Civil War Guns, William B. Edwards Stackpole Company, Harrisburg , PA 1962

2. Civil War Pistols of the Union with Details of Their Service with the Confederacy, by John D. McAulay, Andrew Mobray Inc. Lincoln , RI 1992 pg 10.

3. Civil War Pistols of the Union with Details of their service with the Confederacy by John D. McAulay, Andrew Mobray Inc. Lincoln , RI 1992 pg 11-12.

4 . Civil War Guns, William B. Edwards Stackpole Company, Harrisburg , PA 1962

Sources

Firearms of the American West 1803-1865, Louis A Garavaglia and Charles G Worman Albuquerque, 1984.

Secret Firearms: An Illustrated History of Miniature and concealed Handguns, John D. Walter. Arms and Armour Press, London,1997.

The Complete Handgun: 1300 to Present, Ian V. Hogg illustrated by John Batchelor. Gallery Books, New York City 1979

Antique Guns: The Collector's Guide, John E. Traiser

Pistols of the World: Fully Revised 3rd Edition, Ian Hogg and John Weeks

Pollard's History of Firearms, Claude Blair

Flayderman's Guide to Antique American Firearms and their Values, 7th Edition, Norm Flayderman

The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Handguns: Pistols and Revolvers of the World 1870 to Present, A.B. Zhuk