Lefaucheux Revolvers and The American Civil War

Read More Articles:

Casmir and Eugene Lefaucheux's Advancements in Pistol Design and Their Impact on the War Between the States

(Originally Published in the Civil War Courier)

The most popular revolver during the Civil War by both sides was without a doubt the Colt Army and Navy models. However, there was really no official side arm. As a result, one can amass a relatively large collection of various models. One of the more irregular weapons that were purchased by both the Union and Confederate Armies during the Civil War was the Lefaucheux Revolver. What sets this weapon apart from most of the other revolvers issued was that it was a pin-fire model. U.S. Ordnance records show that 359,000 revolvers were purchased in this country. Although 90 percent of the revolvers supplied were American made by Colt, Remington and Starr there were still 14,000 pistols purchased in Europe. Of these, 12,000 were of the Lefaucheux design. Confederate records suggest that 1,000-1,200 Lefaucheux's were purchased.

The story of the Lefaucheux revolver actually dates back to 1832. It was this year that a Parisian gunsmith by the name of Casimir Lefaucheux produced the one-part pin-fire cartridge. He patented this new style ammunition that was loosely based on the same principles of Johann Nikolsaus Dreyse's needle gun system. Lefaucheux's improvement to fixed ammunition (a case containing cap, primer, propellant and tipped with a bullet) was significant because it was the first example that solved the problem of breech obturation to prevent gas escaping. The Lefaucheux cartridge was composed of a cardboard body with a brass base. The base expanded under pressure of the propellant gas and thus sealed the gap between the chamber and the breechblock. As a result of this seal, the propellant gas had no means of escape besides through the barrel behind the bullet. This significant advancement led the way to much more powerful weapons. The increased momentum would eventually belittle the big bore arms such as the Enfield rifle-musket which had large calibers (.577) to make up for the loss of propellant.

Casmir Lefaucheux advancements in weaponry did not end with fixed ammunition. He patented a "pepperbox revolver" in 1846. This distinctive style weapon had six barrels rotating around a central axis. The cluster was unlocked turned by hand, and then locked into position upon each firing. In addition, the gunman would need to recharge the pan and re-cock the hammer. This was a slow process but still faster than continuously reloading single shot pistols.

Casmir Lefaucheux's ammunition further improved this early style revolver in terms of its loading which was another serious disadvantage. In order to reload a pepperbox, the barrel cluster needed to be removed. The gunman was then required to fill the barrels with a measure of powder. He then had to ram a spherical lead ball down each barrel. This also took a great deal of time. Casimir's fixed ammunition eliminated this step along with the need for a pan and was thus a significant improvement. As a result of his fixed ammunition, he was able to bore the barrels all the way through and they were thus loaded from the rear.

He also produced a breechloading rifle with drop down barrels that was designed and used primarily for hunting. Casimir, like other great revolver inventors Robert Adams, and Samuel Colt broke onto the world market in 1851 at the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park. This was the sight of the Great Exhibition in London, which was devised to bring "works of industry from all nations together." Casimir's large assortment of weapons were greeted with enthusiasm.

However, even before the London Exhibition pin-fire ammunition had been improved by another Frenchman. Bernard Houllier, recognizing the potential of the fixed cartridge, designed a thin metallic case made of copper to replace Casimir's cardboard. Mr. Houllier patented this improvement the year after Casimir patented his pepperbox. Yet Bernard did not do a great deal to implement this ammunition and therefore seldom receives much recognition for the improvement. He is also accredited in this patent with the invention of a rimfire cartridge. However Flobert has received full recognition for the 1845 rimfire which was also displayed in Hyde Park.

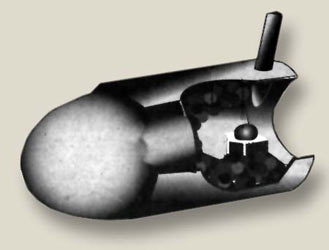

As has been tradition, Casimir's son Eugene Gabriel Lefaucheux followed his father's lead in the invention and production of firearms. On the 15th of April, 1854, following his father's success at the Crystal Palace, Eugene patented a pinfire revolver in France. On April 27, of the same year, J.H. Johnston, a London patent agent, secured British Patent No. 955 for a pinfire revolver. Although Johnson never listed a name for his client, it is certain that it was Eugene Lefaucheux. In Johnson's application the "complete specifications" included most features of the French model. The London patent's specifications lists the revolver as a six-chambered, gate-loaded, single action weapon, with a sliding cylinder bolt thrust forward into recess at the rear of the cylinder by the act of cocking, a rod-ejector at the right of the barrel.

As with his father's pepperbox, Eugene's creation was a breech loader. However, he utilized a specialized hinged loading gate on the right side of the recoil shield, which opened to insert the pinfire cartridges. It helped ensure that the pinfire cartridge was aligned with the hammer.

Europeans quickly embraced the new weapon, and in 1856 the model 1855 system Lefaucheux was adopted by the French Navy. Italy followed suit two years later and soon after Sweden, Norway, Spain and Romania were also supplying their forces with this style ordnance. It was popular primarily because it was an uncomplicated weapon. This simplicity also made it cheap to produce. Because of its production costs, numerous Belgian manufacturers, primarily in Liege, began to produce it for the non-combat market. Germany and Austria also saw an opportunity to profit with the production of pinfire revolvers. As a result, by 1867 400,000 pinfire revolvers had been produced in Europe.

Although, a rather large number were purchased by the U.S. Government in the Civil War, the pinfire craze really never crossed the Atlantic. They were not very popular in Great Britain either, and as a result few were produced there. No pinfire revolvers were produced in the United States, and both of these countries favored percussion revolvers.

The Navy model of 1855 had a length of 6 and a half inches and a weight of 34 ounces. This model had the small caliber of .427 or 11mm. It was a six shooter that shot at a maximum velocity of 650 feet per second. This was slower than most shoulder arms of the day, but it was still one of the more powerful handguns of the time.

The 1853 model which was the arm purchased most widely by the U.S. in the Civil War was similar to the 1855 version in most respects. The largest difference between the two was that the 1853 had a larger caliber of .43 or 12mm. The biggest difference in appearance between them was the spurred trigger guard found on the Army models. The Navy arm had an elliptical trigger guard. Both models have an open frame without a top strap and round grips equipped with a lanyard ring. Although the Lefaucheux barrel shape is sometimes found to be octagonal, the models purchased by the United States forces were round.

The United States Ordnance department first tested the Lefauceux system well before the outbreak of the war. On May 22, 1857 Major Bell from the Washington Arsenal reported that the Lefaucheux revolver would be a practical arm for the cavalry. On April Fools Day, 1858 Major Bell stated that a Lefaucheux was fired twelve times and performed exceedingly well for the limited extent of firing. Major Bell found the weapon to be reasonably accurate. Yet he did not draw any conclusion on the firearm, and as a result none were obtained.

Since both the Butternut and Blue forces were faced with a large deficiency in small arms, it was decided during the onset of the war that arms would in fact have to be obtained in Europe. On July 29, Cameron informed Colonel George L. Shuyler that President Lincoln had selected the Colonel as the agent for procurement of small arms in Europe. Schuyler was given a two million-dollar line of credit deposited in a London Bank to procure 100,000 rifle muskets with bayonets, 20,000 sabers, 10,000 carbines and 10,000 revolvers.

He arrived in London in August of 1861 and stayed there for approximately a month. Colonel Shuyler then traveled to France. While in Paris, during October Shuyler met with Eugene Lefaucheux and was able to purchase 10,000 Model 1853s at a price of $12.50 each. He also purchased two hundred thousand 12 mm cartridges costing $17.45 per thousand.

Many of the various manufacturers of Lefaucheux system revolvers have no identifying marks. However, Lefaucheux revolvers that saw service in the Civil War can be identified. The serial numbers from this large purchase range from 25,000 to 35,000. Another way to identify the arms from this purchase is with the mark LEFAUCHEUX PARIS in a semioval on the left side of the frame.

Revolver's from this transaction were by no means the first purchase of Lefaucheux revolvers. The first such purchase took place on September 28, 1861. The firm Herman Baker and CO. delivered 52 revolvers at a price of $20.04 each. In late November 86 Lefaucheux were secured from George Raphael at a price of $16 each. In March of 1862, Raphael made another sale of 138 revolvers of the Lefaucheux system. Major of Ordnance Hagner also had his hand in the procurement of the French revolvers. In December of 1861 he requested from Alexis Godillot of Paris the second largest procurement of pinfire revolvers. He ordered 2,000 Lefaucheux revolvers with fifty cartridges each, at a cost of $17. In his purchase order he made the ridiculous request that they be provided in no more than 35 days. One thousand five hundred of these arms were delivered on May 31, 1862, and the remainder of the order was never filled. In total the ordnance department had obtained from abroad 12,639 revolvers and 842,880 pinfire metallic cartridges costing a total of $17,039.

Most of the weapons were sent west and issued to state militia or volunteer regiments. Although popular in Europe, for the most part, American troops were not particularly impressed with the pinfire revolvers. In September of 1862, the 5th Kansas was one of the regiments ordered to turn in their existing arms which were composed of Sharps' carbines and some obsolete muskets. The 5th then received a delivery of some Hall's carbines sabers and the Lefaucheux revolvers. The men all seemed to hate the new revolvers. Sergeant August Bondi of Company K was one good example. In his diary he wrote, "The Lefaucheux were worthless, would not carry a ball over fifteen steps, were condemned French arms."

The 5th Kansas couldn't complain too much about their Lefaucheux revolvers. After all, they did at least receive ammunition for them. The 2nd Kansas, which was supplied with 30 of the revolvers on April 20, 1862 didn't receive any pinfire cartridges to go with them. Apparently the required ammunition for these specialized revolvers was far too removed and difficult to obtain for the armies on this side of the Atlantic. Later, the 5th Kansas gladly traded in their pinfires for Colt Navy revolvers. Apparently they weren't the only ones. In the last day of 1863 there were only 124 Lefaucheux revolvers in storage at Fort Riley, Fort Randal and Fort Marcy. In November of 1864, there were 594 in storage.

The troops disliked the weapons for a variety of reasons besides the fact that ammunition was difficult to obtain. The most noteworthy still had to do with the ammunition and its design. Unfortunately, in actual combat situations, this ammunition could not withstand the trials of daily routine. The pin could be struck by accident resulting in a misfire even when the round was not in the cylinder. This would tend to make a soldier with a pouch full of the fixed ammunition somewhat nervous.

There were also some major defects in the design of the revolvers. These problems were the flimsy method for assembling the barrel to the frame along with the shoddy cylinder bolt. Eugene Lefaucheux designed the revolver so that the barrel was screwed onto the end of the cylinder axis pin and locked into position with an indexing screw turned through the front of the barrel lug and into the frame. This made for easy manufacturing which was partially the reason for the revolver's commercial success. Unfortunately though, due to this design these weapons were easily rendered useless by any blow that could bend the cylinder-pin. When considering combat situations, this is a serious flaw in design. After all, the secondary use of a revolver was as a club.

In addition to the trouble with bent cylinder pins, wear and tear on the threads of the cylinder-pin caused by normal dismantling could also damage the weapon beyond serviceable use. The way in which the barrel was aligned with the cylinder was also a source of trouble for the revolver. If the cylinder didn't quite line up with the barrel, upon discharge, bullets would strike the barrel off center. This was both dangerous and inaccurate.

Most all manufacturers attempted to align each chamber with the barrel by using a small lump on the top of the trigger. When the trigger was pulled this lump rose through a hole in the floor of the frame and engaged several lugs on the rear of the cylinder. The cylinder of a pistol with an action that was still tight could not be rotated when the action was cocked. This was because the trigger lump prevented rotation one way while the hand rubbing against the teeth prevented the cylinder from backing off. A good theory in concept, but wear and tear, rust, dirt or congealed oil were all ample opportunities for the cylinder and barrel to misalign. It really wasn't until well into the Civil War that any of the numerous manufacturers seriously addressed these issues.

One of the more minor complaints regarding the Lefaucheux pinfire revolver relates to the means by which the empty cases were ejected. Removing spent shells was accomplished by raising the loading gate and knocking them out with the sliding rod ejector that was mounted below the barrel. This is a relatively time consuming operation.

With all of these design flaws in mind it is no surprise that the average cavalryman was not satisfied with his Lefaucheux revolver. Although a few Lefaucheux remained in service throughout the war, these numbers were slim. Under General order 101 dated June 1865, enlisted men were allowed to keep their side arms. Only 23 of the pinfire revolvers went home with the soldiers. Some of the rest of them were auctioned off at Government Sales of Small-Arms and Other Public Property. One such auction took place at the Leavenworth arsenal, Kansas, on Monday November 25, 1867.

At this auction 19,551 small arms including Lefaucheux revolvers were auctioned off. On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean the problems with the Lefaucheux revolvers were finally being addressed. In fact, by 1863 Alexander Guerriero, Genoa recognized the defect and patented a correction. His improvement was a removable cap fastened to the rear of the cylinder. This cap prevented the pin from being struck by the hammer should the cylinder be misaligned with the barrel. Other manufacturers narrowed the width of the hammer so that if the pin was off center at all. The hammer simply missed the pin completely.

Unfortunately for the European manufacturers, these improvements were really too little too late in the eyes of the Americans who were quite satisfied with their Colt style revolvers. Some more substantial improvements to the pinfire weapons were made by the Belgian Company in Liege, A. Franocotte. These included a change to a double action system.

The Civil War left American weapon manufacturers ahead of their European competition in many ways. The pinfire revolver is just one example of nineteenth century Europe's tendency to stick with outdated ideas which ultimately benefited the United States Economy.

End Notes

Civil War Pistols of The Union, John D. McAulay Andrew Mowbray Inc. Lincoln, Rhode Island. 1992

Guns of the American West, By Joseph G. Rosa, Crown Publishers. Inc. New York, NY 1985

The Complete Handgun 1300 to Present, Ian V. Hogg Illustated by John Batchelor Gallery Books, New York, NY 1979

The Civil War Military Machine, Ian Drury & Tony Gibbons Smithmark Books New York, NY 1993

The New Encyclopedia of Handguns, Christopher Chant Gallery Books, New York, NY 1986 Antique Guns 1250-1865, Robert Wilkinson-Latham Arco Publishing CO. New York, NY 1977

A Study of Colt Conversions and Other Percussion Revolvers, Bruce McDowell, Krause Publications, Iola, WI 1997

Arms & Equipment of the Civil War, Written and Illustrated by Jack Coggins, The Fairfax Pres, New York, NY 1962

Military Small Arms: 300 years of Solders' Firearms, Edited by Graham Smith Foreward and Introduction by Ian V. Hogg Salamander Books Limited London, England 1996.

Arming the Union, Small Arms in the Civil War, Carl L. Davis National University Publications Kenikat Press Port Washington, NY 1973#