The Patriot and the Parrott Cannon

Read More Articles:

Captain Robert Parker Parrott

and the Parrott Cannon Greatly Influenced the Outcome of the War Between the States

(Originally Published

in the Civil War Courier)

The Parrott Rifle was an important artillery piece to the Union, and to a certain degree, Confederate forces. This stemmed from low production costs, accuracy, and power. The weapon was a key contributor in demonstrating the shortcomings of masonry fortifications. It was invented by a steadfast unionist, Captain Robert Parker Parrott, just prior to the war.

Captain Parrott was an extremely honorable man, who was greatly devoted to his country, and its union. Robert was born October 5, 1804 in Lee, New Hampshire. He enrolled in the West Point Military Academy in July of 1820. There, Capt. Parrott was very successful, as he was throughout his life. He graduated with honors in 1824 and was third in his class. He was assigned to the Third Regiment of Artillery with the rank of Second Lieutenant.

His success in academics caused him to justly work at West Point between 1824 and 1829. At the Military Academy he served a wide variety of positions starting as Assistant Professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy. He then worked as assistant Professor of Mathematics. Parrott finished off his five-year tenure at West Point as Principal Assistant Professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy.

After his prolonged stay in West Point, Robert P. Parrott was sent back to his home state where he served in Fort Constitution for two years. He was then promoted to First Lieutenant on August 27, 1831 and subsequently transferred to Fort Independence, Massachusetts where he remained until 1834. At this point, Parrott was moved to the Southeastern United States. His obituary states that he was involved in "staff duty in military operations in the Creek Nation." However it would have been impossible for Parrott to see any action in the 2nd Creek Indian War of 1836 because he was appointed Captain of Ordinance and was ordered to Washington as Assistant to the Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance on January 13, 1836. Settlers' homesteads fell victim to frequent attacks from Creek militants during the early 1830s. However, the first large scale battle in the 2nd Creek Indian war took place on January 26, 1836 near Bryants Ferry on the Chattahoochee River in Georgia.

Captain Robert Parker Parrott

Captain Parrott remained in the position of Assistant to the Chief of Ordnance for exactly 10 months. Governor Kemble convinced Robert Parrott to take over the position of Superintendent at The West Point Foundry in Cold Spring, NY some time prior to October 13, 1836.

The West Point Foundry was located just across the Hudson River from the academy. It was here that Parrott designed and forged the first Parrott Rifle. The idea of rifling was familiar to those interested in the matters of ordnance prior to the Civil War. The concept was simple. The grooves of a rifled cannon forced the projectile to fly in a spiral motion. This allowed the ammunition to travel greater distances and hit its target with higher accuracy and with more power. Parrott's creation was significant because it expanded the life of rifled cannons. Prior to the Parrott rifle, most cannons were constructed of bronze. Although bronze was a strong, stable material for cannon manufacture, it was relatively soft. Therefore, the rifling grooves would rapidly wear down until they were useless. The obvious solution to this problem was to produce cannon tubes entirely of cast iron. But iron had its drawbacks, too. It tended to be very brittle and was prone to crack under heavy use. These cracks would inevitably burst under the pressure of propellant gasses. In the field, cannons that experienced such a mishap would injure, and in many cases, kill its crew.

What Robert Parker Parrott did to counteract the tragic side of an iron cannon, makes the weapon easily distinguishable to Civil War enthusiasts today. Parrott attached a wrought iron band to the breech end of the gun to reinforce the breech. The process of reinforcement was relatively simple as well. It started out with a 60 inch long bar of iron about four inches square. The bar was heated red hot, coiled around a mandrel and welded by a large trip hammer to close the circle. The reinforcing band was heated once again and placed over the tube. The tube was rotated horizontally on rollers while the band cooled in place. As the coiled iron bar cooled, it contracted around the tube. This allowed the band to clamp uniformly about the breech giving the gun strength and durability.

In addition to being strong, the Parrott cannon was a remarkably cheap weapon to manufacture. It only cost $187 for the West Point Foundry too produce a 10 pounder Parrott rifle. Just as importantly, it was produced quickly and in quantity at the Foundry. The cost and effectiveness of the Parrott cannon kept the West Point Foundry's furnaces in operation around the clock. There were three shifts for laborers who were allowed eight hours rest in boarding rooms. The same beds were rented out to all three shifts. Therefore, if a worker became ill, he still had to work because someone else was in his bed.

The first Parrott rifle manufactured by the foundry in 1860 was a 10 pounder. At this time, Captain Parrott was still tinkering with bore diameter and the number of lands and grooves in the rifling. It was sent to the State of Virginia, which need them as a result of John Brown's Raid at Harper's Ferry. Professor Thomas Jackson tested a Parrott at the Virginia Military Institute. He fired the cannon at tent flies which were set up on a nearby mound and found the weapon to be of high standards. Union Forces soon cornered the market on weapons produced in West Point Foundry though. Not that Mr. Parrott would have sold his wares to Confederate forces anyway. He said, "If I were a younger man I should return to the army, and do what I could to aid my country there; but at my age, and position I am denied the opportunity of helping the government in that way. However, in this way I can be of use and I intend that these guns shall cost the United States no more than is absolutely necessary."

Robert Parker Parrott's design more than made up for his absence from the front. It proved its value to the United States early on in the war at Fort Pulaski. The fort was the chief defense of Savannah Georgia. It was located on Cockspur Island and was casemated on all five sides with 71/2 inch thick walls. The stronghold was further protected by deep channels that put a mile of water between the island and any solid ground. Colonel Quincy Adams Gillmore challenged General Totten's opinion that "The work could not be reduced in a month's firing with any number of manageable calibers." Gillmore set up some Parrotts along with a few James rifles on Tybee Island. The guns smashed the walls into piles of rubble and yellow dust. The Confederates gave up the post on April 11, 1862.

Two and a half months later President Lincoln paid a visit to Capt. Parrott at the foundry in Cold Spring. Lincoln attended a demonstration in the proving ground where Parrott displayed the capabilities of two of his newer models. A 100-pounder, along with a 200-pounder, fired heavy shells at a rugged peak called Crows Nest. The Hudson Highlands around Cold Spring all endure the scars of persistent battering from the guns produced in the West Point Foundry. Lincoln's tour of the foundry was a productive one for Robert Parrott. Three days after the presidential visit, 100 and 200-pounders were shipped off to McClelland's army, which was near Richmond at the time.

The Seven Days' Battle, further proved the significance of the Parrott rifle. Until this point, the major Southern producers such as Tredgar Iron Works were still pumping out 12-pounder howitzers, 3-inch rifled guns and 6-pounder smoothbores. In fact, Tredgar's greatest rate of production took place during the month of April prior to this battle. Anderson & Company produced 72 cannon in this one month. These were primarily 6-pounders and 12-pounders. Southern churches woefully sacrifice their bells for these tubes. After the climax of The Seven Days Battle, Malvern Hill proved once again the superiority of Union Artillery over Confederate pieces. The Confederate batteries, which were set up as a diversion for Union artillery, were pounded piece by piece. Not a single serviceable Confederate gun with a direct line of sight remained in action by 2:30 p.m., just one half hour after the barrage began. Therefore the churches sacrificed in vain. Furthermore, every charge the South attempted to make up the bloody slopes of Malvern Hill was repulsed by the superior Union guns before the Confederates were even in range with their muskets. 5590 Confederates fell on that early July afternoon to the fiery breath of Union gunners and their Parrott rifles.

As a result of Malvern Hill the Confederate Ordnance Department acted quickly to improve their artillery. Thomas S. Rhett, Ordnance Inspector, told Anderson & Company to start producing seven 30-pounder Parrotts on July 11. These were to be patterned after a Federal Gun seized at First Manassas. The Confederates named this captured gun Long Tom. Soon after on July 26, the first Confederate Parrott was cast. Just four days later, the Tredgar Iron Works were further instructed to produce 20-pounder Parrotts as well. These turned out at the end of August, but no Parrott-designed tubes were in the Southern artillery's hands until September.

The West Point Foundry out produced Tredgar Iron Works throughout the war. This stemmed mostly from the South's inability to acquire the required natural resources. Although the early models of the cannon varied, Robert Parrott settled on a diameter of 2.9 inches and 3 grooves by 3 lands in 1861 when the United States started ordering them. The weapon's overall length was 78 inches and it had a slight muzzle swell. However, by 1863 Parrott changed the diameter once again to an even three inches and also did away with the muzzle swell.

At the time of the outbreak of the war, the West Point Foundry was producing 20 and 30-pounder rifles. The 20-pounder had a diameter of 3.67 inches and rifling of 5 grooves by 5 lands. Its overall length was 89.5 inches. The 20-pounder model was not a popular piece with the army. It was too small in scale and precision of fire to make for effective siege piece. Yet the 20-pounder was also too heavy to make for an effective field piece.

The 30-pounder Parrott had a diameter of 4.2 inches and was rifled with 5 grooves by 5 lands. A 30-pounder's overall length was 132.5 inches and it weighed 4,200 pounds which was carried on an 18-pounder siege carriage. The Navy also used some 30-pounder Parrotts. However the Army model was too large and heavy for convenient use at sea. Therefore, these weapons were manufactured at 112 inches overall length and weighed only 3,550 pounds. This weapon was known to break its elevating screws, but still remained popular as a siege piece. This was because the screws could be removed, and the gun could still be used with accuracy.

The weapon also made for an excellent sniping rifle. The 30-pounders were faster and easier to fire than the heavier guns. Although not as powerful as the heavier arms, they were able to work against the Southern gun placements, distracting them. This distraction caused Confederate forces to fire wildly and inaccurately. With the reduced threat of an accurate Southern bombardment, Union gunners on the larger caliber guns were able to concentrate their efforts on accurately firing rounds.

One 30-pounder Parrott rifle took part in the siege of Charleston for 69 days. Quincy Adams Gillmore, who was by this time a General, described the piece in detail in the official records. It was mounted on Morris Island about 6,600 yards from the city. This weapon fired 4,505 rounds, and 4,494 of them reached the city. The most rounds this piece fired in a single day were 157, but it averaged around 97 shots a day. When it did finally burst, it broke into seven pieces. This was by no means the only piece to burst on Morris Island. Twenty-three other Parrotts suffered the same fate.

In the summer of 1861 Captain Robert Parrott had developed a 100-pounder with a 6.4 inch diameter. The overall length of this weapon was 155 inches and it had a weight around 9,827 pounds. In the Winter of 1862 West Point Foundry turned out its first 200-pounder with a diameter of 8 inches. They had an overall length of 162 inches and weighed 16,537 pounds. The Navy also tried their hand with this arm, but like the 30-pounder, it was also shortened for naval use. Length for arms made specifically for the Navy were 136 inches and fired a 152-pound shell. These Navy arms can be easily identified by the anchor, which is found on the tube between the trunnions. The Navy looked on the large caliber arms with much disdain. They were prone to bursting. In fact, when the Union Navy attacked Fort Fisher in December of 1864 several Parrott rifles burst killing and wounding 45 sailors. Confederate fire only claimed 11 Union sailors in that engagement. The news of these tragic occurrences forced Captain James Alden of the U.S.S. Brooklyn to move his two 100-pounders to the side of the ship that was not facing the fort.

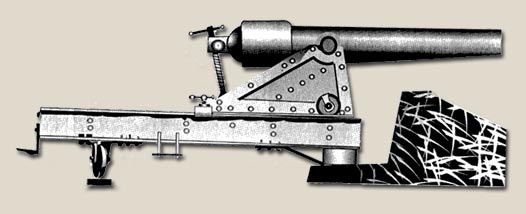

While the 10, 20 and 30-Pounder Parrotts were usually mounted on Wooden Carriages, the heavier siege models were sometimes mounted on Iron Front Pintle Barbette Carriages as this 100-pounder is.

The 200-pounder guns were capable of being fired at distances between four and five miles. However, the Navy needed weapons with high accuracy at short distances, and this the 200-pounder Parrotts could not deliver. Especially not when the ship which carried them was tossed about by the sea. In fact, while on a stable platform, the 200-pounder was only accurate within a two-block radius. Not surprisingly, during the War Between the States, the Navy still preferred a smoothbore cannon to rifled. This was because a round shot fired from a smoothbore cannon would skip across the water and still make contact with its target if it fell short. The shell from a rifled cannon required complete accuracy and needed to hit its target from the air in order to be effective.

The Army was much more forgiving in regards to the larger caliber Parrott's tendency towards bursting. This was because of the weapon's capability of pounding its way through strong masonry fortifications at great distances.

The largest Parrott rifle produced by the West Point Foundry had a caliber of 10 inches and fired a 300-pound projectile. These 300-pounders weighed 26,900 pounds and were rifled with 15 lands and grooves. Only three Parrotts of this caliber were utilized in the War Between the States. All three of them saw service in the Siege of Charleston. One of them fired on Fort Sumter at 4,290 yards away. After only a few firings, a shell burst inside the tube breaking off 18 inches of the muzzle. The cannon was still operational however. The jagged remains of the muzzle were chipped into a more uniform configuration and the cannon fired another 370 rounds at about the same range and accuracy.

Ammunition for rifled cannon was a difficult item to design. At the time of the War Between the States, muzzle loading cannon were still the most reliable style. However, a system of projectile needed to be designed that could fit down the muzzle and still mold to the shape of the lands and grooves so as to produce the desired spiraling effect upon firing. This problem in design was addressed with a variety of solutions.

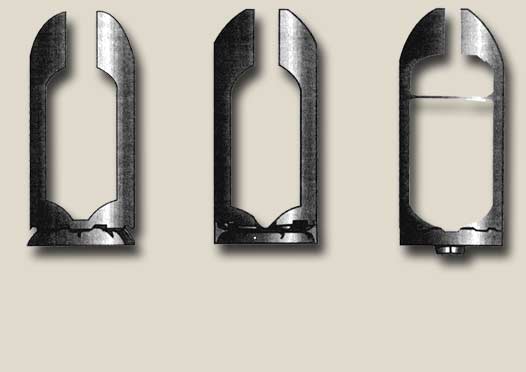

Left: Early Parrott Shell with Brass Sabot that indents at the bottom. Center: Parrott Shell with improved Sabot Notices the Flush casing. Right: Incendiary shell created for Berney's incendiary projectiles. Notice the two compartments. The top section contained a charge. The larger chamber was used to fill six pints of Berney's "secret" composition. The bolt on the bottom was used to fill the chamber. A fuse would be screwed into the Ogive of all these examples.

Prior to the war, Robert Parrott was associated with Dr. John Brahan Read (often incorrectly spelled Reed) from Alabama. In 1856 Read patented a projectile with a sabot or metal cup at the base which upon firing could take the grooves of the rifling. The way the Southerner manufactured this form of projectile was by placing the sabot in a mod and casting the projectile around it. Read used wrought iron to create the sabot originally, but later changed it to copper. In times of sacrifice and substitution, the cup was even cast in lead. In this case it is believed that the casting process needed to be changed to accommodate the soft material. The Union forces found sabots made with these materials to be inferior. Therefore, the shells made at West Point Foundry utilized brass cups. The first shells that were made used an indented brass cup. Later versions utilized a flat cup that was flush where it attached to the rest of the projectile. This too was made of brass, but still had one chief difference when compared with the previous models. Indentations were cast into the base of the projectile to keep the sabot from turning while it was fired.

Robert Parrott made shells for all the calibers of his rifles, from 2.9 to 10 inches. Aside from differences in diameter, they generally appear the same. There were a few differences for the 100 and 200-pounder versions however. For these short and long models were available.

A Parrott Shell

The Sabot was obviously an important part of the projectile. However, equally important was the means by which a shell was timed to detonate when it reached its target. For this the Parrott time fuse was necessary. The Parrott time fuse used a Zink plug threaded on the outside. The inside of this plug was conical and housed a paper fuse that could be cut to the needed length. Parrott shells also used a percussion style fuse. As opposed to time fuses which were set upon discharge; percussion fuses were triggered upon impact. The Parrott shell's percussion fuse was largely based on experiments conducted at West Point. In these experiments a nipple was attached to a piece of metal. A standard cap was placed on top of this contraption. The cap would be dropped into the projectile and a metal head was screwed on before the shell was loaded into the cannon. The percussion cap would stay in its stagnant position while being loaded and hurled through the air. However on impact, it slammed forward into the metal headpiece and sent a flame down the center channel, which led to the charge. Robert Parrott further modified the West Point experiment by creating a self-contained plunger. This plunger's headpiece attached directly to itself instead of to the body of the projectile. Parrott also filled it with powder to give it more power.

Left:

300-pounder step bolt Actual Weight 222 pounds

Right:

200-pounder Round Ogive Bolt Actual weight, 150 pounds

Bolts were also used in Parrott rifles and came in two general styles. Although both had a blunt ogive, one version rounded to the flattened nose, while the other had more of a step. In all there were about 35-40 different style bolts, these solid projectiles were used to pound their way through ironclads. Parrotts also used an experimental form of incendiary ammunition. This somewhat dubious ammunition is often called Greek Fire. Like the idea of rifling, Greek Fire was also a familiar concept prior to the War Between the States. It had been used previously by the Russians to deter Napoleon's attacks, and was not a new concept even to them.

Levi Short and Alfred Berney produced two differing styles of this implement of war. When the incendiary shells were produced, they required two separate compartments. The top compartment housed a bursting charge while the bottom compartment was filled with the secret composition. Berney's version required 6 pints of the composition for a 100-pounder shell. It is believed that Berney's Greek fire was a combination of turpentine and petroleum and when ignited, it burned at 1200 degrees.

The Swamp Angel, perhaps the most famous Parrott rifle, used Berney's as well as Short's version of Greek Fire in the siege of Charleston. The Swamp Angel fired its first blazing shot of Greek Fire at 1:30 a.m. on August 22, 1863, and set fire to a warehouse. In response to this and the 14 shots that followed, General Gillmore's opponent General Pierre, G.T. Beauregard said, "a number of the most destructive missles ever used in war (were sent) into the midst of a city, taken unawares and filled with sleeping women and children."

Although highly controversial to both the press in the U.S. as well as to residents of the Confederacy, the shells were of little effect. The Swamp Angel fired 12 Berney and 24 Short Shells. Six of Short's creation exploded in the barrel of the Swamp Angel. After firing only 36 rounds, the Swamp Angel burst at its breech sending the remainder of the tube flying onto the Marsh Battery's parapet of sand bags. Short's shells earned a terrible reputation, but Berney's product fared no better. The Berney shells exploded in midair never reaching their target. Although the Greek Fire may have caused a premature burst in the Swamp Angel, The 200-pounder Parrott rifle's design certainly was partially to blame. During the Siege at Charleston, 3 other 200-pounder Parrotts positioned on Morris Island also burst at the vent in the same exact way that the Swamp Angel did. These models were sent to Trenton, NJ to be melted down. One of them was saved, and it is believed by some to be the Swamp Angle. However, the authenticity of this piece has fallen under a great deal of scrutiny.

After the War Between the States, the Parrott cannon was no longer of any real service to the Army. Steel began to replace cast and wrought iron as the optimal material for use in artillery. Moreover, vast improvements in breech-loading arms were quickly making muzzle-loaders obsolete. There were attempts to modify existing Parrotts into breechloaders, but none of these proved successful.

Robert Parker Parrott opted not to complete the last contract he had made with the Federal Government, even though it would have been in his own financial interest to do so. The Union army agreed that this was best for they no longer needed them. In 1867, Parrott gave up the foundry. However he never stopped trying to improve fuses and projectiles until his death on December 24, 1877.

Bibliography

Artillery and Ammunition of the Civil War, by Warren Ripley

Lincoln and the Tools of War, by Robert Bruce Captain

Robert Parker Parrott, by Jack Melton as seen at http://www.cwartillery.org/parrott.html

Iron Maker to the Confederacy, by Charles P. Dew

The Civil War Fort Sumter to Perryville, by Shelby Foote

Field Artillery Weapons of the Civil War, by James C. Hazlett Edwin Olmstead M. Hume Parks

Arms & Equipment of the Civil War, by Jack Coggins

Weapons of the Civil War, by Ian V. Hoog

The Civil War: The Struggle for Tennessee Tupelo to Stones River, by James Street Jr. and the Editors of Time-Life Books#