A Dentit's Innovations: Dr. Edward Maynard's Tape Primers and Carbines

Read More Articles:

Dr. Edward Maynard's Tape Primers and Carbines were welcome Improvements to the Design and Function of Firearms In an Age of Experimentation

(Originally Published in the Civil War Courier)

When going to the dentist, it is odd to think that the person responsible for some of the advancements key to good oral hygiene could also have created one of the more deadly arms of the American Civil War. Of course anyone who has had a couple of teeth filled or a root canal could probably see the similarity.

Dr. Edward Maynard was born on April 26, 1813 in Madison New Jersey. To those familiar with United States' military history he is most well known for two of his inventions. The first of which is the Maynard tape primer and the second is the Maynard Carbine. However, his work in dentistry is equally compelling. Probably his most significant innovation in the world of dentistry is the practice of filling cavities with gold foil. Today however, there are probably more skirmishers using Dr. Maynard's weapon systems than there are dentists filling teeth with gold. That practice is almost as long gone as the days of the Civil War.

At the age of 18 Edward had aspirations of becoming a soldier. In fact, he entered West Point. Unfortunately, he was forced to resign the next year because of poor health. He then took up the study of dentistry in which he was successful. Dr. Maynard practiced in both the United States and Europe. His abilities as a dentist were respected enough to land him a teaching position at the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery and the National University in Washington DC. Although his success as a dental surgeon certainly brought him much fortune, the Dr.'s work in the field of firearms was more lucrative.

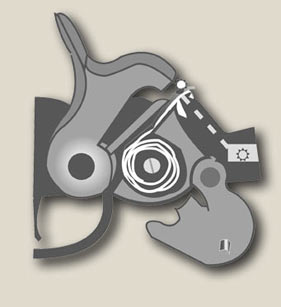

Maynard's most significant invention involving firearms is the Maynard tape primer. He earned a patent on September 2, 1845 for this invention and it was quite successful. Of all the priming devices patented in the 1840s and 50s Maynard's was the most widely used. The mechanism is comparable to a roll of caps used in toy guns. Maynard's design used a priming strip with spots of mercury fulminate placed equidistant between two long narrow strips of paper. The strips were glued together and varnished as a way to waterproof them. The composite strip was then rolled up so that it could fit into the actual mechanism. Each strip contained 36 charges.

Arms that included the tape primers in their design had a magazine which can be described #as a circular recess in the lock plate. This was where the tape primer was stored. When the hammer was cocked, the tape was pushed forward by a toothed wheel. This positioned the fulminate cap on top of the cone and simultaneously cut off the paper behind the exploded cap. As with the traditional copper percussion cap, the flash of the explosion was jettisoned through the cone. From there the flash entered the main charge in the breech and caused the all-important explosion and gas expansion that sent the projectile flying. The rather successful design was applied to new arms and also was used to modify flintlock muskets.

The Ordnance Department took immediate notice and interest in Maynard's tape primer design. In 1845 the government purchased the rights to apply it to 4,000 muskets at $1 per musket. This was just the first of many such applications involving the invention. On February ninth of 1848, and once again in November of the same year, Dan Nippes from Mill Creek Pennsylvania received a similar contract. Nippes was to do some work for the Ordnance Department which involved converting 1,000 flint muskets to the Maynard primer system. Mr. Nippes' weapons can be identified by the stamp on the magazine cover which states "EDWARD MAYNARD PATENTEE 1845" or "MAYNARD'S PATENT WASHINGTON 1845". The hammer of the arms had a straight shank to fit the protruding straight upper left edge surface of the magazine cover. The weapons fitted with Maynard's tape primer were somewhat experimental and were used in field trials. Most of the muskets converted in Mill Creek were shipped to Texas and New Mexico. The Texas unit, Company A of the Eighth Infantry was receiving shipments of the arms by the spring of 1850. The arm was reviewed by Lt. G.A. Williams of the First infantry as, "Far superior to any of the many inventions seen where the object to be obtained is a rapid succession of fires." 1

There were, however, some complaints. The first of which was that the men felt the priming strips were not waterproofed well enough to withstand a single nights guard. This was a key problem with Maynard's tape primer system and would eventually lead to its decline. The other complaints seemed to result form Mr. Nippes' modifications. One major problem was that a single blow of the hammer could set off three of the fulminate spots at once.

Apparently though, these complaints did not completely eliminate the importance of Maynard's tape primer. The government decided to pay Dr. Maynard $50,000 in three installments of $16,666.66, on February 3, 1854. This bought the rights to Maynard's primer and permitted unreserved use of the system for the Army and Navy. Subsequently, the U.S. Government used the Maynard tape primer on rifle muskets produced between 1856 through 1861. The primer system was not included in the design of arms produced during the War Between the States because the tape primer's themselves did not withstand the tests of inclement weather.

The limited success of the tape priming system is not Dr. Maynard's only claim to fame in regards to innovative firearm design. His breechloading arms were not as widely recognized as a significant advancement in weaponry. However, they were one of the more accurate and reliable breechloaders during the Civil War. The dentist initially patented the arm on May 27,1851 with patent number 8,126. This arm was extremely complicated. Therefore, it was further refined with patents in 1856 and 1859. Patent number 15,141 covered the Maynard metallic cartridge. Maynard called the unprimed cartridge a "metallic cup." It has been credited as the first such device to use the expanding cartridge case as an effective gas seal.

The good Doctor's cartridge was comparable to the one used by the Burnside. Both examples utilized a small central flash hole which permitted the initial flash, produced by a percussion cap, to ignite the powder. Another characteristic helpful in identifying Maynard's ammunition is the unusually large rim which allowed the spent case to be manually extracted. The rim was riveted or soldered onto the cylindrical case.

Perhaps the greatest advantage of these cartridges was that they could be reloaded. However, doing so required Maynard Reloading Accessories. In a Navy test of the ammunition, the metallic cartridges were reloaded 200 times, and still serviceable. Theoretically though, should necessity have arisen, the arm could be loaded with no cartridge, by simply using loose ammunition. In this case, the ball would be inserted first at the breech, and then followed with a cartridge or charger filled with a flask for each shot.

The calibers of Maynard arms common during the time period of the Civil War were .35 and .50. The cartridge contained a bullet, which by itself was 343 grains of lead. It also held 40 grains of powder.

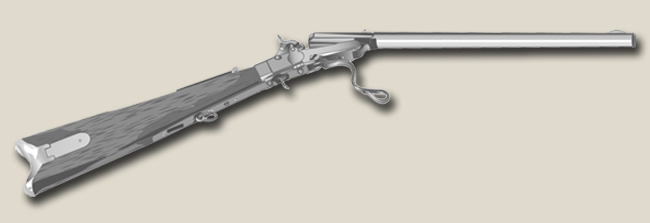

The early model carbines had a length of 36½ inches and weighed about 6 pounds. Moreover, there was no forearm on the weapon. However, the appearance of the nicely crafted barrel, which measured 20 inches made up for it to a certain extent. At the breech of the blued barrel, there was a five inch octagonal section which tapered to a cylinder. Near the muzzle sat an iron blade front sight. It was matched with a two leaf rear sight which was graduated to 500 yards. Versions produced later have a sling swivel on the lower trigger plate.

Dr. Maynard utilized his patented tape primer magazine in his design. It was placed on the right side of the receiver. The tape primer was complimented with an iron patchbox to keep the tape roles dry. The metal cover for the patchbox was secured to the stock by a hinge connected to a thick iron buttplate.

A keen eye will find the serial number of these early arms when one opens the primer door and takes a look inside. Other stamps are on the breech-frame. On the right side is marked, MAYNARD ARM CO./WASHINGTON. Then turn the fine weapon over to the left side and discover, MANUFACTURED BY/MASS. ARMS CO. CHICOPEE FALLS. The patchbox door is marked, MAYNARD PATENTEE/MAY 27, 1851/ JUNE 17, 1856. In addition, the earliest of the first models have an added date SEPT 22, 1845 on the patchbox.#

Four hundred early model Maynard carbines were ordered by the Ordnance Department on December 25, 1857. All of the arms were of the .50 caliber model and were used in various testing situations. The rifled carbines were all in the governments hands by March of 1859.In this same year the Navy gave the arms a trial. Commander John Dahlgren oversaw the test firing of the carbine in the Washington Navy Yard. There, Dr. Maynard demonstrated his .50 caliber weapon by firing it at a 3x6 foot target. It was placed 200 yards away, and 237 rounds were discharged. The test was extremely successful in that the target was never missed. Just as importantly, after 562 discharges, without being cleaned, the arm suffered almost no fouling. This certainly equated to a durable weapon suitable for an exhaustive campaign. It also had a relatively high rate of fire at 12 rounds per minute. The Navy was obviously impressed with these tests and purchased another 60 in February of 1860. Some of them are known to be issued to Marines aboard the U.S.S. Saratoga.

Just one month later, the Army conducted tests of its own. Nine varieties of carbines were examined by the trial board. The Maynard faired quite well in the board's review; it took second place in fact. The Smith was perceived better in overall serviceability for the cavalry. The trial board's chief complaint with Dr. Maynard's arm was that the hammer and tumbler were one unit. The board feared that this would lead to difficulties. The board also felt that the cartridge rim should be bigger. It was decided that the arm should be adopted in small numbers for fieldtesting.

With this in mind, some of the arms procured were sent to the St. Louis Arsenal. Sixty of these were later issued from Ft. Union, in Mexico Territory to the Regiment of Mounted Rifles. The regiment's Lt. Col. gave the Maynard carbine a glowing review on July 14, 1859. He was generally pleased with its rate of fire, which was found to be 10 rounds per minute. He also appreciated how easy it was to load the arm due to its metallic cartridge.

Dr. Maynard's weapon saw some of its first true field service during Indian conflicts involving the 1st Cavalry. Co. I of the 1st Cavalry received 143 of the arms in 1859. One hundred more of them were distributed to Co H also of the 1st Cavalry in 1860.

The Southern States were by far the larger consumer of Mass. Arms Co.'s merchandise during the onset of the War Between the States. In the months that immediately preceded the war both the .35 and .50 calibers were purchased. In fact, when the Confederates eventually issued ordnance manuals, the Maynard was listed as an official weapon.

One cannot really consider, James T. Ames and Sylvanus Adams, owners of the Mass. Arms Co., as the most loyal citizens to their country. The opportunists used the ominous clouds of war as a chance to get rid of their great inventory. As despicable as it may seem by today's standards, this was a fairly common practice of the time.

The Mass. Arms Co.'s profits came from a variety of Southern states. The state of Mississippi is known to have purchased 325 carbines in .50caliber and another 300 in .35 caliber from the company. Georgia purchased 650 Maynard's in .50caliber as well. Around 800 carbines of varying caliber were shipped to several different militia groups in South Carolina and Louisiana. The state of Florida bought more weapons from the company than any other Southern State with their order for 1000 carbines in .35caliber.

Of course, these were still terribly meager supplies compared to what was required to arm the Confederacy. General Ben McCulloch was facing a desperate situation in June of 1861. It appeared that the Federal army would be invading Arkansas and Indian Territory and McCulloch's forces were dreadfully under-equipped. The cavalry had to take matters into their own hands. In order to procure some decent weaponry, they placed ads in the Fort Smith Daily Times and Herald requesting that citizens sell them Maynard carbines along with other choice weapons.

The early model was still being sold in the North as late as 1864. During this year, the weapon could be ordered through the catalog of a New York City outfitter, Schuyler, Hartley & Graham. This is rather surprising because as early as December 6, 1859 Maynard patented his improved breechloading firearm with patent #26,364. The further refinements of the arms produced after 1859 were unbelievably well conceived. The working mechanism was housed in a very compact form. Dr. Maynard managed to design each feature to the smallest possible occupation of space. Yet, the apparatus did not lose any of its strength.

The Improved Maynard Breech Loading Mechanism

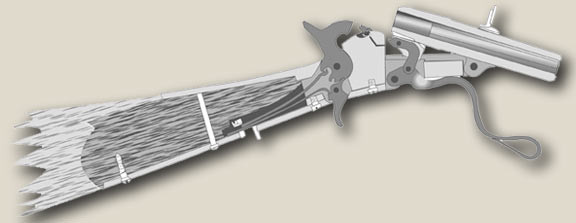

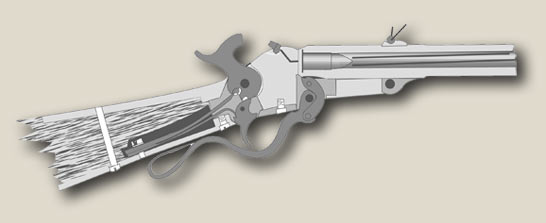

The improved version of the breechloader left the barrel mounted on a strong transverse pivot located at the front of the frame. A large lug was situated underneath the barrel at the breech. It was connected by a toggle link to a lever which was mounted on its own frame pivot. The lever of course doubled as a trigger guard.

Both the early version and the later version were operated in the same general way. By pulling the lever/trigger guard in a downward and forward motion, the breech end of the barrel was forced upward. This enabled easy loading.

The second version of the Maynard carbine had a few more subtle changes. On the early version there was a tang sight. This was disposed of on the later models. In addition, the earliest models had a sling swivel. However, most of the arms sold to the Confederacy did not have this feature. A sling ring was later reinstated on the models produced in the early 1860s.

The most obvious difference between the arms though involves Dr. Maynard's earliest innovation to firearms. Although the diagram for patent #26,364 shows plans for the Maynard tape primer, the models produced by the Massachusetts Arms Co. for the United States Government dropped the mechanism. With its exclusion, the elimination of the patch box obviously followed. The stock was also squared off, and a thinner butt plate took the place of the heavy iron one which was so prevalent on the earlier models. The black walnut woodwork on the second version of the firearm took a beating from some critics because of its simplicity. It was described in 1862 as having, "a lank appearance, as if sawed from a board, which I think most men will agree with me…" 2 There were other complaints regarding the Maynard besides its cosmetics. Critics from both the Union and the Confederacy found the weapon to be way too light for its charge. This resulted in a tremendous recoil especially in the .50 caliber models. However the .35 caliber charge wasn't quite as bad. It is somewhat baffling to consider that the second version produced for the U.S. government persisted as a .50 caliber arm.

As the demand for arms increased, and the obvious advantages of breechloading arms became clearer, the U.S. government placed a substantial order with the Massachusetts Arms Co. In June of 1863 General Ripley drew up a binding agreement with the company's agent, T.W. Carter. The company was to produce 20,000 Maynard carbines at $24.20 each, and they had to produce them fast. In fact the contract stated, "The whole of these twenty thousand carbines and appendages are to be delivered within 12 and 18 months from the date of this contract." But what good is an arm without ammunition? None at all! So that is why the Government ordered 2,157,000 Maynard cartridges. The sum of this order was $72,207.50

Massachusetts Arms Company wasn't quite as fast as the contract required, but they did manage to complete the order in a relatively timely fashion. The first delivery wasn't received by the United States until June 22, 1864. After this delivery, the company was able to hand over 1000 carbines about every two weeks. The final delivery of 960 carbines was made on May 19th, 1865. Since the arms were not received until well after the Confederacy's High Water Mark, they were not widely used by the Union Forces. However, there were a few Union cavalry regiments armed with Maynards. The 9th and 10th Indiana, and the 11th Tennessee were a few lucky recipients.

Because the second version was procured by the Union towards the end of the conflict, many of the arms were stockpiled and later sold off. Therefore, collectors can often find them in good condition at a relatively affordable cost. The production of Maynard style firearms continued well after the American Civil War. Sporting rifles called "Model 1865" were really originally produced in 1863 at the same time the contracts with the war department were being produced. Following the war, the company wisely used incomplete or unfinished actions, which were originally intended for military carbines for the private market. The Model 1873 was the first Maynard to utilize a center-fire metallic cartridge.

End Notes

1. Firearms of the American West, 1803-1865 pg 115, Louis A. Garavaglia and Charles G. Worman

2. The Breech-Loader in the Service: 1816-1917 pg. 84, Claud E. Fulller

Sources

Identifying Old U.S. Muskets Rifles and Carbines, by Colonel Aracadi Gluckman Carbines of the Civil War 1861-1865, by John D. McAulay

The Pitman Notes on U.S. Martial Small Arms and Ammunition 1776-1933 Volume One Breech-loading Carbines of the United States Civil War Period From Original Materials Drawn and Collected, by Brig. Gen. John Pitman

Civil War Firearms: Their Historical Background, Tactical Use and Modern Collecting and Shooting, by Joseph G. Bilby Single Shot Rifles, by James J. Grant

Arming the Union, by Carl L. Davis

Arms and Equipment of the Confederacy, by the Editors of Time Life Books

Firearms of the American West, 1803-1855, by Louis A. Garavaglia and Charles G. Worman

Fighting Men of The Civil War, by William C. Davis and Russ A Pritchard

The Civil War A Narrative Fort Sumter to Perryville, by Shelby Foote

The Big-Bore Rifle, By Michael McIntosh

Guns of The American West, by Joseph G. Rosa

Illustrated Encyclopedia of 19th Century Firearms, by Major F. Myatt MC #