The Sharps Carbine and Those Who Made it Famous

Read More Articles:

The Sharps Carbine & Those Who Made it Famous

(Originally Published in the Civil War Courier)

Of all the arms used in the War Between the States, only a few earned legendary status. With nomenclature like Beecher's Bibles, the arms designed and manufactured by Christian Sharps were destined to obtain this level of notoriety.

However, a legend is a long time in the making, and the story of the Sharps arms goes back a long way. In fact, to truly understand the history of this successful breech loader, you need to remember as far back as 1788. It was then that Captain John Hancock Hall was born in Portland, Maine. It was on May 21, 1811 that a patent was issued to Captain J. H. Hall and the young Washington architect William Thornton. This patent reflected that they were the first U.S. citizens to create a breech-loading long arm.

By 1812 the breech loading mechanism had been improved so as to withstand the force of a heavier powder charge as required for military service. A series of tests were conducted in 1813 and 1816. Then a year later, a order for 100 "patent rifles," were ordered at a cost of $25 a piece. These rifles were intended for field tests and they faired well in March of 1819. Hall spent the next two years in the Harpers Ferry Armory perfecting the mechanism. As a result Captain Hall was awarded a contract for 1,000 rifles. In order to ensure that these arms were properly manufactured, Hall was given a position at Harpers Ferry as Assistant Armorer. There he earned $60 a month and $1 on every weapon manufactured.

In addition to recognizing the importance and advantage of breech-loading arms, Hall is also credited as the originator of interchangeable parts for firearms. While at Harpers Ferry, he designed and built several machines which enabled parts to be produced at an accelerated rate and at the same time create uniformity between them. These machines ensured his place in history. Unfortunately though, the construction of these machines delayed production until 1824. 20,872 Hall breech-loading rifles were made at the Harpers Ferry Armory; an additional 1,700 were made by private contractors over Captain Hall's objections.

Breech-loading long arms had several advantages. The Halls were easier to load, especially when finding one's self in a difficult position. Loading a gun from the breech was much easier than doing so from the muzzle, especially while lying on the ground. Moreover this relaxed method of loading was also beneficial when on horse back. Fumbling with powder charges was next to impossible while in the saddle. Breech-loading also reduced the risk of overloading an arm which was a common mistake in the panic of a combat situation.

Although these arms were a great step forward, they were not very well liked by the troops. First off soldiers were generally conservative and attached to their muzzle-loading arms. Even in 1862, Chief of Ordnance General Ripley still preferred the rifle musket over breech-loaders for infantry. However, the largest grudge against Hall's creation was its loss of gas. This resulted from the fact that the block was not tightly locked upon the barrel in firing position, and therefore allowed an abundant amount of gas to escape between the chamber and barrel. Although largely a Mexican War Era arm, the Model 1833 and 1843 Hall, saw considerable use by the cavalry in the Civil War particularly, in 1861 and 1862. Most Yankees considered them to be worthless because in addition to the tendency to burst, spewing flaming powder and hot gas, they did not carry well and were quick to fall into disrepair. The Confederates found a suitable use for Halls by salvaging many of their parts from the Harpers Ferry Arsenal fire. The enterprising southerners also modified some of Halls arms into muzzle loaders.

In a remarkable coincidence, Christian Sharps was born in New Jersey in 1811, the same year that Hall patented his breech loader. Sharps eventually ended up working with Hall in Harper's Ferry in 1830. There Christian learned the intricacies of every one of Hall's rifles and carbines. Just as importantly, young Sharps learned the basics of assembly line production techniques. However, he clearly saw the need for improvement in Hall's mechanism. Therefore in about 1840, while working for himself in Cincinnati, Ohio, he improved Hall's breech-loading system.

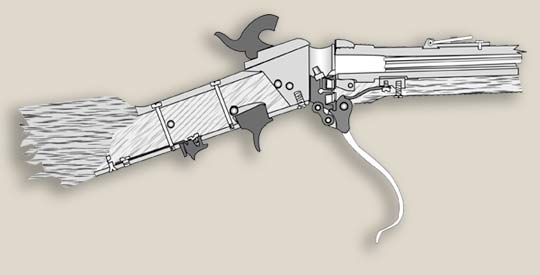

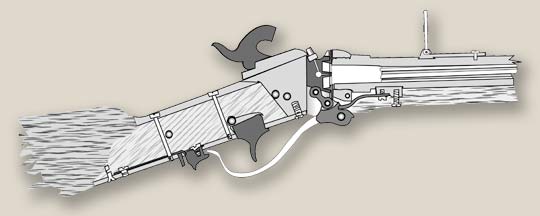

The top diagram the arm is in loading position while the bottom is loaded

The following years saw Christian diligently experimenting with variations in breech mechanisms. On September 12, 1848 as a result of these arduous studies, a U.S. Patent was obtained. The patent describes a, "gun with sliding breech-pin and self-capping." Sharps solved the problem of leaking gunpowder in the breech with the use of the drop block. The Sharps rifle had a small block in the breech of the gun that slid up or down in a slot. This was controlled by a lever which served a second purpose as a trigger guard. When the trigger guard was lowered and pulled forward, the block slid into position, opening the breech for loading. When the trigger guard was closed, the mechanism raised the small block up into the breech. The drop block sealed the breech and greatly reduced the escape of gas and the threat of backflash. This eliminated most of the complaints which seemed to accompany the use of Hall's arms. However, although fast sturdy and reliable, Sharps' arms still leaked some fire at the breech.

An added advantage of Sharps' rifles was that in addition to the tight seal, an edged blade was screwed to the face of the breech-block. This cut the linen or paper cartridge exposing the powder and thus setting up the rifle for the next stage of firing. The cone or nipple was then ready for primers fed by Dr. Maynard's tape primer system and later the R. S. Lawrence disk primer magazine. An additional feature was that the primer magazine could be shut off if needed and ordinary caps could be substituted.

The earlier models had a sloping breech action with the hammer swung inside the frame. As the design of these arms progressed, the hammer was moved to the outside.

These arms were manufactured for a brief stint in 1850 and 1851 in Mill Creek, PA. However, the arm is associated more widely with the Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company which was established in about 1851 at Hartford Connecticut. Weapons were made there in accordance with Sharps' patents. The plant was managed by R.S. Lawrence.

In 1853 Christian Sharps left the Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company and moved to Philadelphia. Christian Sharps was only loosely connected with the plant. In actuality his only affiliation was the $1 per rifle royalty which he earned for each Sharps arm made there.

Christian once again started his own small shop at 336 Franklin Street in 1856 while living at 486 Green Street. Apparently the royalty fees from Connecticut did not add up to a substantial profit, because he needed capital to expand his operations. Therefore, Christian formed a partnership with Ira B. Eddy. The firm was known as Eddy, Sharps & Company. In 1856 the operation was moved to a four story brick building on the west side of 30th street measuring 140 feet by 40 feet. A more general description of the operations new location would be on the west side of Philadelphia.

Each floor of the structure served a distinct purpose. The first floor safely housed the heavy forging operations, while the second floor was dedicated to barrel production. The third floor was utilized for tool making, and the fourth floor was where the small parts were manufactured and the final assembly took place. In 1858, Nathan H. Bolles became a partner, and the name was once again changed to C. Sharps and Company which it remained until 1863.

The arms produced in these early years were clearly appreciated by military personnel. Some of the Model 1848 .52 caliber carbines were issued to the 1st Regiment of Dragoons in 1853. They were immediately popular. Capt. J. W. Davison in command of Company B wrote the Ordinance Department saying, "I am satisfied from trial and experience that the Sharps' carbine is the best weapon yet known in our country for a cavalry soldier. Its range and accuracy are greater than those of the musketoon. It is a stronger arm; the soldier can make it last longer… The Sharps' can be loaded at full speed… I am satisfied that the horseman needs no pistol, if armed with Sharps' carbine and a light and sharp sabre." These are great praises for a somewhat experimental weapon, and they were backed by other officers.

During the Kansas-Missouri Border Wars, the arm was further raised to legendary status by Reverend Henry Ward Beecher. Beecher was somewhat of a militant, and has been quoted as writing, "there are times when self-defense is a religious duty. If that duty was ever imperative, it is now, and in Kansas." According to popular legend, he promised to buy members of the Wabaunses colony a rifle and a Bible. Beecher's congregation shipped model 1853 Sharps' Carbines into Kansas in cases with 25 rifles and 25 bibles. Supposedly, some of the arms arrived in cases marked BIBLES. This brought about the somewhat paradoxical title Beecher's Bible. Many modern historians seriously scrutinize this folklore today, but it has no doubt only perpetuated the legendary status of Christian Sharps' arms.

Beecher was by no means the only Sharps toting man with abolitionist ideals. John Brown also put faith in the Sharps' "miraculous powers." He and his followers carried them on their famous raid on Harpers Ferry Arsenal on October 16, 1859.

In January of this same year, Sharp secured patent #22,752 which covered the R.S. Lawrence disc primer. The Lawrence device allowed a brass tube of waterproofed primer discs to be inserted into the frame on the right side by moving a screw at the bottom of the lock plate. The disks were continuously fed by the forward movement of the hammer. This model also saw the advent of .50 caliber rimfire ammunition. This patent did not change the frame or breech mechanism of the old Sharps percussion system. However, the factory made some alterations. The firing pin was retracted by a shoulder, sliding in a slanting groove in the frame. The shell was removed by a lever pivoted below the chamber. This lever was forced into action by the downward movement of the breechblock.

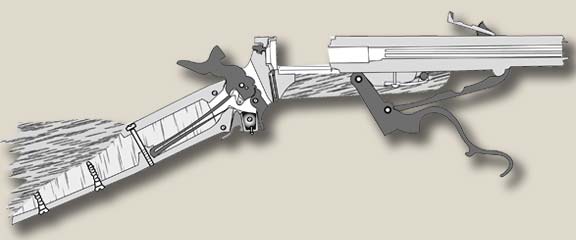

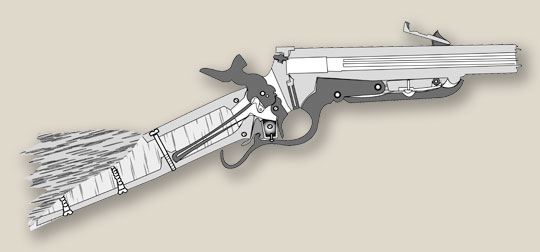

Top details the mechanism durring loading the bottom displays the mechanism while cocked and loaded.

In 1860 another newcomer entered the firm, William C. Hankins. Mr. Hankins became superintendent of the firm and was needed for his capital and his experience as a wood-maker. Ira Eddy and Nathan Bolles left the firm a year later.

On July 9, 1861 Christian Sharps applied for a patent on a new action and a hammer safety mechanism. The new action utilized a sliding barrel. By depressing a stud under the frame and swinging the trigger guard lever downward, the barrel was caused to slide forward along a metal track. Just 11 days later, Lieutenant R. Wainwright of the Navy Department fired an Old model Sharps rifle 500 times. Unfortunately there were 15 failures caused by faulty rimfire ammunition.

The test must have been largely interpreted as positive though. The Sharps Company quickly found itself having difficulty meeting the demand required for the arms by the military. In December of 1861 General Ripley put out an order for all the carbines Sharps could manufacture until further notice.

In 1862 Hankins became a full partner, but the firms name did not change until 1863. However, the ordinance department clearly recognized Hankins as a partner. A specific example of this is in orders from General Ripley to Major Laidly dated on July 22, 1862. SIR: The Secretary of War having accepted the offer of Messrs. Sharp & Hankins, of Philadelphia for 250 of their improved carbines, you will please inspect and receive each of them as you may deem suitable for the service. You will also procure from these gentlemen two hundred cartridges for each arm, a peculiar kind being required. The price named by theses gentlemen in their offer is $25.00 per arm; $20 per thousand for the cartridges. It is understood that suitable appendages and packing boxes will be supplied by the makers without additional cost to this department. Respectfully your obedient servant, J.W. Ripley. Brigadier General, Chief of Ordnance.

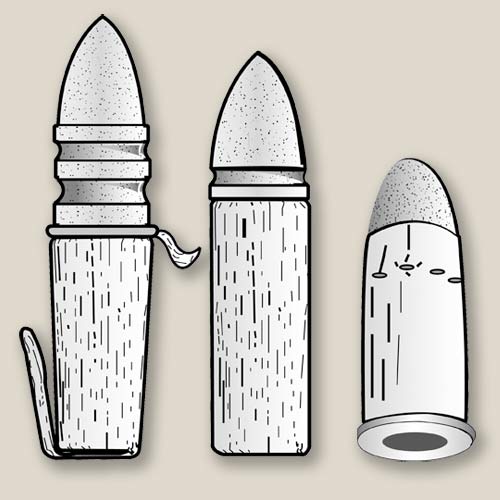

Left: Paper, Center: Linen, Right: Rimfire

It was in 1862 that the improved New Model of Sharps & Hankins carbine came into production. The chief difference between the two models was the design of the firing pin and hammer. The Old Model utilized a firing pin as part of the hammer. The New Model had a floating firing pin in the receiver. The majority of the carbines utilized in the War Between the States were of the New Model (1862) type. The earlier models fired a .52 caliber rimfire cartridge while later models were chambered for .56 caliber in order to be compatible with the Spencer rimfire cartridge. The Sharps' carbine's barrels were blued and had a length of 385/8 of an inch for the Army and Navy models. The arm measured an overall length of 331/2 inches long. Sharps & Hankins also produced a 331/2 inch total length cavalry version complete with sling ring on the left side of the frame. These were used primarily by the 11th New York Cavalry. The Sharps carbine was the most widely used arm by the Northern cavalry for the first three years of the war.

Clearly the U.S. Ordnance department had some interest in the Sharps' arms. However, the extent of this demand would not be fully realized immediately. It seems in retrospect that as the arm's fame grew in the U.S. Civil War, so did its demand. Certainly one of the individuals responsible for bringing the arm to its legendary status quickly became a legend himself. Hiram Berdan and the 1st and 2nd United States Sharp Shooters (U.S.S.S.) probably did as much to popularize the arm as anything. Berdan quickly found himself and the regiments he led as media darlings. The press immediately cozied up to the green and blue clad force. Ironically, the controversial leader's first choice of weaponry for his elite division was not a Sharps. In fact, it wasn't even a breech loader. In mid July 1861 he wrote General Ripley requesting Springfield rifle muskets.

This is somewhat confusing because an advertisement in the Minnesota Central Republican on December 11, 1861 stated "All able bodied men used to the rifle…will be… furnished with subsistence & comfortable quarters, …as soon as they present themselves. Will use Sharps improved Breech Loading Rifle."

It is possible that the popular figure around Camp of Instruction, Private Truman Head of Company C had already sold the rest of the Sharpshooters on the Sharps' rifles. Truman, who is better known as "California Joe," was just as popular with the press as Berdan. In fact there is at least one known photo with the two men together. The gold and grizzly hunting California Joe purchased his own Sharps while at Camp of Instruction near Washington D.C. in September of 1861.

After close inspection of California Joe's Sharps, which was a New Model 1859 equipped with a saber bayonet, it quickly became clear that the U.S.S.S. would accept no substitutes. To say the least Berdan was in a difficult spot. He had already requested the Springfields. Moreover, Ripley was not too keen on arming any branch but the cavalry with breech loaders. This stemmed from his desire to eliminate the "great evil" attributed to many different kinds, as well as caliber of ammunition. As early as September 21st, 1861 Col. Berdan had telegraphed Richard S. Lawrence of the Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company "When will the sample rifle be here without fail. Answer immediately."

Whether or not Joe's rifle or the one requested by Berdan was the deciding factor in equipping the Sharpshooters is unclear. What is certain however is that in late October Berdan wrote in a letter to Secretary of War Cameron,

The nerve of Hiram Berdan was amazing, though. Rippley would not allow the deal to go through because R.S. Lawrence was already backed up with carbine orders for the cavalry. Berdan didn't let that stop his mission. In November just a month after the correspondence with Cameron, he ordered Colt Revolving Rifles in a bizarre political maneuver to acquire Sharps. Hiram Berdan pulled the weight of Col. R. B. Marcy, Chief of Staff to the Army of the Potomac's commander General McClellan, McClellan himself, and even Abraham Lincoln whom, he had met at a target practice.

When the 1st and 2nd regiments initially received the Colt revolving rifles, they were not happy. Many men signed up believing that they would be receiving Sharps. In fact some privates decided to take the matter into their own hands by writing congressional representatives about the situation. Berdan considered this action to be a "mutiny."

Some members of the 1st U.S.S.S. marched off to war without any rifle at all rather than accepting the dangerous Colt revolving rifles. However, the 1st U.S.S.S finally received their highly sought Sharps in May of 1862. The 2nd was soon to follow, as they were given theirs in June of the same year.

The arms these young men coveted are known as Berdan Sharps Rifles. They are the standard New Model 1859. This model had the 30 inch round barrel, straight type breech design with exposed S shaped hammer. Three oval barrel bands hold the forestock in place. All of the furniture is made of iron and these rifles have no means to receive a sling bar. Carbines are the only Sharps weapon with that feature. However there were a few subtle differences with the Berdan Sharps. The Berdan Sharps is fitted for an angular socket bayonet with no separate locking lug near the muzzle. A more obvious feature is that these arms were fitted with a double set trigger. Pulling the rear trigger set the hair trigger in front of it so that the slightest movement would send the hammer falling. This little gizmo eliminated the need for a locking latch to hold the lever closed. The locking latch was required on single trigger rifle 1859 models.

The exploits of the legendary U.S. Sharp Shooters are vast and well documented due to the Civil War era press' fancy with them. The Sharps weapons certainly did meet Berdan's prediction that, "with these weapons we can not only make a name for ourselves but be of vast service to the country."

Although primarily a U.S. weapon, the Confederacy too had a few Sharps, and they were highly sought (particularly the U.S. versions). On December 28th, 1861 at the Battle of Sacramento Kentucky, Nathan Bedford Forrest was engaged in his first action of the war. After Union forces moved up 100 yards towards Col. Forrest in what appeared to be the beginnings of a charge he was quick to take advantage of the situation. "…I dismounted a number of men with Sharp's carbines and Maynard rifles to act as sharpshooters…," he reported.

In the mad dash to arm itself prior to the War Between the States, Southern arsenals were able to purchase 1,600 of the Sharps' arms legally. Of course the South also did its best to capture the arms. However, in many cases this proved to be difficult. One of the advantages that the Northern forces saw in this weapon was that it could be quickly disabled. This was done simply by removing the breechblock by a single pin. The Breechblock could then be discarded. This left the arm useless, much to the dismay of the ensuing Confederates.

Of course capturing and purchasing weapons were not the only means the South used to arm itself. There was also the blossoming arms industry. The S.C. Robinson Arms Co. in Richmond, VA manufactured 5,000 copies of the Sharps carbine. The Company utilized the standard .52 caliber linen cartridge. Unfortunately, the arms produced between 1862 and the end of the war, were not very popular among the soldiers who used them. Even R.E. Lee was opposed to the arm calling it, "demoralizing to our men."

As always, sacrifice and substitution were the largest problems in the production of the Robinson arms. A specific example of substitution is in the barrel mountings which were made of brass rather than iron. The arms also lacked the Pellet or Lawrence primer attachment. Yet, these were the sort of woes that the South endured in every aspect of manufacture.

The Sharps arms legacy lived on after the War Between the States. It became the rifle of choice to the Buffalo Hunters. Subsequently models were designed thereafter with the sportsman in mind.

In 1867, the Sharps & Hankins factory ceased production. Once again membership in the firm changed hands William Hankins went his separate way. The name was subsequently changed back to C. Sharps & Co and all the arms were sold-out in early 1868. In 1871 Christian left Philadelphia. From there, he and his family, wife Sarah, daughter Satella, and son Leon Stewart Sharps, moved to Vernon, Connecticut. Christian died on March 12, 1874 from tuberculosis.

End Notes

Sharpshooter: Hiram Berdan, his famous Sharpshooters and their Sharps Rifles,by Wiley Sword Lincoln, RI 1988

Guns in the American West, New York, NY 1985

Nathan Bedford Forrest New York, NY 1993 pg 79

Carbines of the Civil War, pg 95; pg 64 for question for lawrence; pg 64 for service to country; pg 63 for poster

Sharpshooter: Hiram Berdan his famous Sharpshooers and Their Sharps Rifles by Wiley Sword Lincoln, RI 1988

Identifying Old U.S. Muskets Rifles and Carbines, by Colonel Aracadi Gluckman

Carbines of the Civil War 1861-1865, by John D. McAulay

The Plains Rifle, by Charles E. Hanson, Jr.

The Pitman Notes on U.S. Martial Small Arms ans Ammuition 1776-1933 Volume One Breech-loading Carbines of the United States Civil War Period From Original Materials Drawn and Colleted, by Brig. Gen. John Pitman

Civil War Firearms: Their Historical Background, Tactical Use and Modern Collecting and Shooting, by Joseph G. Bilby

Arms and Equipment of the Confederacy, by the Editors of Time Life Books

Nathan Bedford Forrest, by Jack Hurst

Fighting Men of The Civil War, byWilliam C. Davis and Russ A Pritchard

Great Century of Guns, by Branko Bgogdanovic Ivan Valencak

The Pictorial History of U.S. Sniping, by Peter R. Senich

The Civil War A Narrative Fort Sumter to Perryville, by Shelby Foote

The Big-Bore Rifle, By Michael McIntosh

Guns of The American West, by Joseph G. Rosa

Illustrated Encyclopedia of 19th Century Firearms, by Major F. Myatt #